Every Kindle has a device name. By default, this is something like “[Your first name]’s Kindle”, but it can be changed by the user. Its primary purpose is to make it easier to distinguish between multiple Kindle devices. Let’s say you own two Kindles and you want to send a book to one of them - you’ll have to select the correct device, and that’s when the device name comes into play.

Given its purpose, the device name has to be displayed within various areas of the Amazon web site.

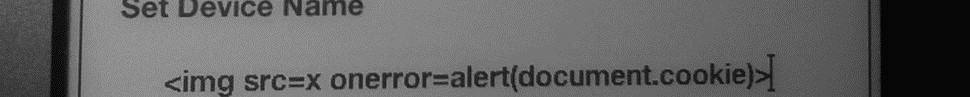

The device name can be changed on Amazon’s web site and on the device itself. If changed on the web site, characters such as < or > will not be allowed; however, the device itself applies no such input filtering. (Enforcing different input rules on different input vectors is actually another problem and may have contributed to the exploitability of the vulnerability described below.)

With the device allowing characters considered to be unsafe in the typical HTML context of a web site, what would happen with a device name such as, say, “<img src=x onerror=alert(document.cookie)>”?

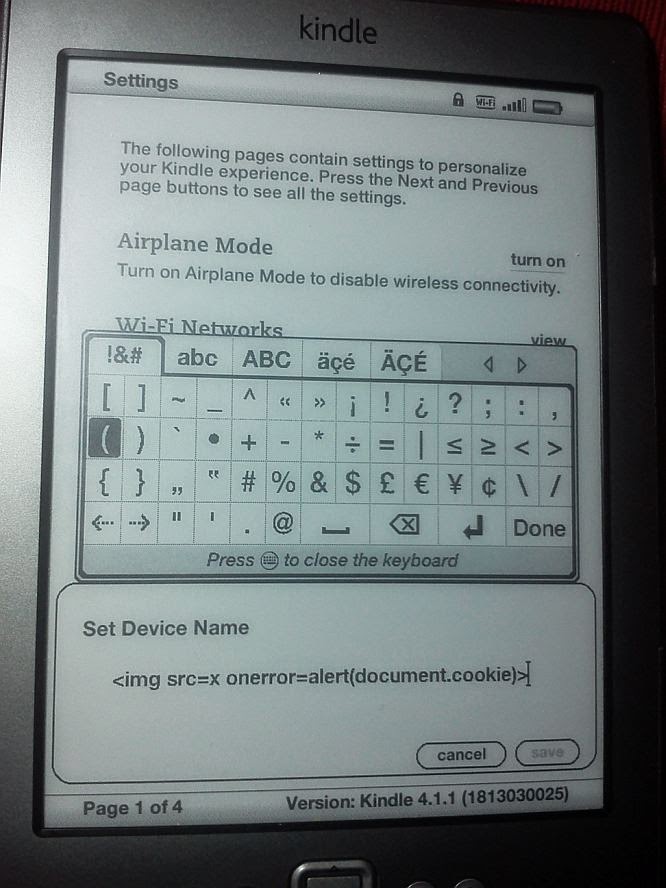

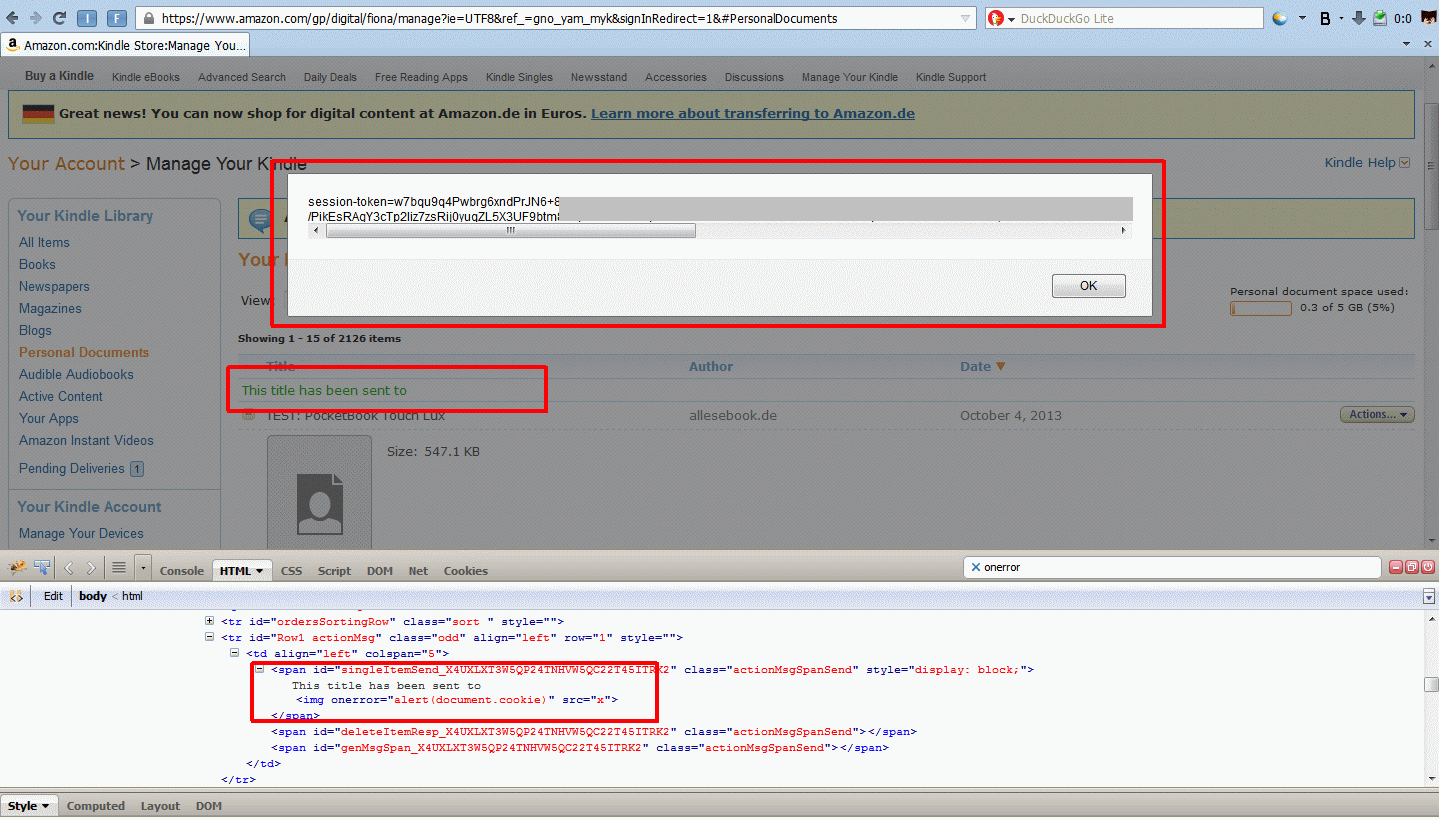

Well, what happened is that whenever the account owner would send a document to this Kindle, the HTML code in the device name became part of Amazon’s “Manage Your Kindle” web page and would subsequently be interpreted in its context:

Because the device name is displayed while a user is logged into the connected Amazon account, this allowed an attacker to access account related cookies. The code would also be executed within Amazon’s “Send To Kindle” widget, which can be embedded into web sites and allows for easy transfer of content to a Kindle (and, in this case, cookies to an attacker).

The vulnerable page most likely to be abused was Amazon’s main contact page at https://www.amazon.com/gp/help/customer/contact-us. Keep in mind that an attacker had to gain physical access to a device in order to change its name to something malicious. Unless the device in question was intentionally shared with the attacker, that meant stealing or finding a previously misplaced Kindle. Both of these events were likely to result in the owner accessing the vulnerable contact page to report the loss, thereby executing the payload.

I first noticed and reported the problem to Amazon in October 2013 and it was fixed shortly after (see timeline below). However, a redesign of the “Manage Your Kindle” page in 2014 reintroduced the vulnerability in a more dangerous fashion. From my email to security@amazon.com:

The issue […] (XSS via Kindle device name) has become considerably worse; the injected code will now be executed without the previously required user interaction (it is no longer necessary to send an item to a device, instead, opening the “Your Devices” or “Settings” tab is sufficient).

Even though Amazon’s Information Security Team didn’t confirm it, it seems that the vulnerability has been closed again - at least for the time being.

If you own a Kindle, setting a lock screen password helps to protect your Amazon account against this and similar attacks. This is why you should use a password, even if the confidentiality of the data stored on your Kindle is not a concern to you, and why you should share the device only with people you trust. Setting a lock screen password is quite easy and instructions can be found here: https://www.amazon.com/gp/help/customer/display.html/ref=hp_k2start_pass?nodeId=200375510&#kpassword

Timeline

2013-10-06 Vulnerability discovered.

2013-10-06 Vulnerability reported to security@amazon.com.

2013-11-15 (No response from Amazon.)

2013-11-15 Sent second report to security@amazon.com.

2013-11-19 Amazon.com Information Security assigns case number.

2013-12-03 Sent third report, adding information about contact page.

2013-12-06 Reported vulnerability partially fixed.

2013-12-19 Reported vulnerability fully fixed.

2014-??-?? Vulnerability reintroduced by “Manage Your Kindle” web page redesign.

2014-07-09 Vulnerability reported to security@amazon.com.

2014-07-?? (No response from Amazon.)

2014-07-?? Reported vulnerability fixed.